Poverty Point Earthworks: Evolutionary Milestones of the Americas

Poverty Point Earthworks: Evolutionary Milestones of the Americas examines the site now called Poverty Point State Historic Site in northeastern Louisiana. The archaeological artifacts discovered at Poverty Point provide evidence of a highly developed ancient American culture that inhabited the lower Mississippi delta between 1750 and 1350 BC. This site includes one of the largest native constructions in eastern North America and the earthworks are the oldest of their size in the Western Hemisphere.

In the 1840s, Jacob Walter, an explorer traveling through the area looking for lead ore, first reported the presence of Native American artifacts on the Poverty Point site. However, the true significance and magnitude of the find was not discovered until the 1950s when an old aerial photograph revealed the incredible size of the earthworks at the site.

By examining the artifacts uncovered at the site, archaeologists determined that the site had been abandoned 3,300 years ago and the society of hunter-gatherers was large and sophisticated. Scientists estimate that the construction of the massive earthworks at the site took millions of hours of labor to complete.

Funding for this program came from the Louisiana Office of State Parks.

All mounds on public land are protected from digging and artifact collecting. Access to all sites on private property is completely under the control of the landowner, and trespassing is forbidden by law. Please help us, the Louisiana Office of State Parks, the Division of Archaeology, and the people of Louisiana, in working together to help preserve and protect the nationally significant mounds of our state.

Program Transcript

For centuries, the Middle East has been considered the cradle of civilization. The acceptance of the 10 commandments on Mount Sinai…the great pyramids of Egypt…the laws of Hammurabi. These are the legacies of Middle Eastern societies that flourished 2000 years before the birth of Christ. Yet, scientists had little evidence that ancient American civilizations were capable of creating such grand works. The discovery of prehistoric earthworks in rural Louisiana has revolutionized historians’ view of the evolution of society in the New World.

Poverty Point Earthworks: Evolutionary Milestones of the Americas

Over the last 50 years, archeologists have explored and excavated numerous Louisiana earthwork sites. Located in northeastern Louisiana, the site at Poverty Point Plantation includes some of the largest American earthworks of the prehistoric period.

Jon Gibson, Ph.D., Archaeologist: "In the lower Ms. Valley there’s a long history of earthwork development that may last probably seven thousand years, maybe 6,500 years, and of all places in the United States this is the one area where the earthworks first came about.”

In the 1840s, Jacob Walters, an explorer traveling through the area looking for lead ore, first reported the presence of Native American artifacts on the Poverty Point site. However, it wasn’t until the 1950s that the discovery of a 20-year-old aerial photograph revealed the site’s unique form: Poverty Point contains a man-made earthen structure so large that it defies recognition from the ground. This revelation eventually lead scientists to uncover new evidence of a highly developed, ancient American culture

For the last 40 years, the Poverty Point site has been carefully excavated by archeologists from all over the country. Piecing together all of the details of daily life in extinct cultures is not an exact science, but an interpretive art. The inhabitants who built the site abandoned the area more than 3,300 years ago. While there are still unanswered questions, archeologists do know many things about where the people lived, what foods they ate and how they made tools. Scientists’ findings are based on three major sources: the earthen ridges; the mounds; and, artifacts found at Poverty Point and at similar settlements in the lower Mississippi Valley. Based on artifacts, scientists also have begun to reconstruct the society’s organization and its government.

Between 1800 BC and 1350 BC, the people of Poverty Point inhabited a region of the lower Mississippi delta.

Roger Saucier, Geoscientist: "I guess we’ll probably never know exactly why Poverty Point people settled exactly where they did. I have a feeling that that is probably largely a matter of socio-economics or perhaps a socio-political factor. But obviously the Poverty Point peoples liked the margins of ridges like Macon Ridge. This has afforded them high ground relatively immune from flooding, with good airable soils and good locations for living conditions. But perhaps more importantly, this enabled them to be immediately adjacent to these very rich bottomland forests and hardwood areas that are so abundant as far as plants and wildlife and fisheries are concerned

At the heart of the Poverty Point site are the earthworks. One of the largest native constructions known in eastern North America, the Poverty Point earthworks are older than any other earthworks of this size in the western hemisphere.

Jon Gibson, Ph.D., Archaeologist: "From here to here….started building them for."

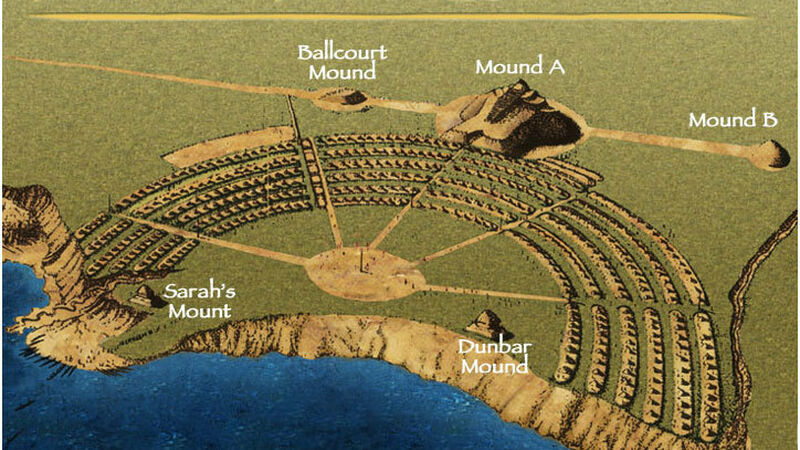

A C-shaped figure dominates the center of the site. The figure is formed by 6 concentric artificial earth embankments. They are separated by ditches, or swales, where dirt was removed to build the ridges. The ends of the outermost ridge are 1,204 meters apart (nearly 3/4 of a mile). The ends of the interior embankment are 594 meters apart.

If the ridges were straightened and laid end to end, they would comprise an embankment 12 kilometers or 7 1/2 miles in length. Originally, the ridges stood 4 to 6 feet high and 140 to 200 feet apart. Many years of plowing have reduced some to only one foot in height. Archeologists suspect that the homes of 500 to 1,000 inhabitants were located on these ridges.

Bob Connolly, Ph.D., Archaeologist: "The PP earthworks were originally constructed around 1800 years BC, but we know that they were not the first earthworks built by Native Americans in Louisiana. For example, nearby to PP, a little bit west of Monroe, LA, the Watson Break earthworks were constructed as early as 3300 years BC. What is important is that we begin to see this continuum of development in the earthwork construction from the time of Watson Break all the way up through European contact when, uh, for example at the Grand Village of the Natchez, the earthworks were still occupied by Native Americans and we actually have accounts, from the original European explorers in the region."

Mounds were still being constructed in Louisiana in the mid-1500s. During the 1800s some mounds in southern Louisiana were used for traditional religious activities. Today the mounds continue to be sacred and powerful places.

In the center of the Poverty Point earthworks is the plaza, a flat, open area covering about 15 hectares or 37 acres. Archeologists suspect the plaza was the site of ceremonies, rituals, dances, games and other public activities. On the western side of the plaza, archeologists have found some unusually deep pits. One explanation is these holes once held huge wooden posts, which served as calendar markers. Using the sun’s shadows, the inhabitants could have predicted the changing of the seasons.

Also located within the plaza are Dunbar Mound and Sarah’s Mount. Evidence suggests Sarah’s Mount was constructed approximately 1,000 years after the decline of the Poverty Point culture.

Outside the ridged enclosure are five other mounds. Mound A and Motley Mound appear to many to be in the shape of a bird in flight.

Dennis LaBatt, Historic Site Manager: "Mound A…pretty impressive." (measurements and basket loads) "You know, if one is to see a bird...carefully laid out." "The bird mound…village area."

Motley Mound may be considered to be unfinished. There is only a small bulge where the bird’s tail should be. Scientists believe these mounds were used for special activities or as a gathering place for the elite.

Mound B is a domed mound 180 feet in diameter and 20 feet in height. Throughout the eastern United States, domed mounds were frequently used for burial. However, no burial sites have been excavated at Poverty Point.

Ballcourt Mound is a nearly square flat-topped mound about 100 meters or 300 feet to the side.

Lower Jackson Mound is estimated to be as much as 1,000 years older than other mounds at the site.

Robert Connolly, Ph.D., Archaeologist: "What this points to is that the PP site was occupied for a longer period of time. What this points to is that people came back to the PP site after the original occupation. And not only continued to conduct activities here, but actually continued adding to the earthworks as well, up to a period of 700 AD."

Besides the construction of the colossal earthworks and mounds, another hallmark of the Poverty Point culture is long-distance trade. Since there were no local stones on the Macon Ridge, rocks were major trade goods. Other materials, such as food, may have also been traded. Due to lack of preservation and soil erosion, little archeological evidence of those goods remains. The people of Poverty Point acquired stones from the Quachita, Ozark and Appalachian mountains and even copper from the Great Lakes–1,400 miles away.

Jon Gibson, Ph.D., Archaeologist: "Rivers were almost certainly used in bringing the trade materials into PP because we’re talking about such a massive volume. In fact, we’ve estimated over 71 metric tons of foreign flint occurs on the PP site."

Some were traded in a natural condition, but many were circulated in finished forms. While some rocks were used to make tools, others were used to create ornaments or symbolic objects. The extensive trade network of the Poverty Point culture is one big difference with the earlier Watson Brake Indians who relied only on local raw materials for manufacturing tools.

Located between the woodlands and the swamplands, the Macon Ridge was rich in plant and animal food sources. Archeologists have recently found evidence of what appears to have been a large lake, where there is now only farmland. The predominance of fish and reptile bones at the site suggests most of their foods came from slow-moving water. Fishermen may have used cast and gill fishing-nets weighted with plummets to capture the fish.

Jon Gibson, Ph.D., Archaeologist: "You really don’t have to angle to catch fish. You could set out a trap and you could set out a net and let the netting do the work for you while you’re coming to work on the rings, while you come and build the mounds, while you go hunting. So it’s kind of an absentee work system, but boy it put a lot of food in their larders."

Besides fish and plants, deer, rabbits, geese, ducks, and turkeys flourished in this habitat.

Hunters stalked their prey with spears. To provide added power and distance, the inhabitants used atlatls, or spear-throwers. Atlatl hooks were sometimes made of carved antler. Polished stone weights were attached to help transfer the force of the throwing motion to the spear.

Foods were prepared with a variety of tools. Animals were butchered with stone cleavers and blades. Nuts, acorns and seeds were pounded into flour and oil with pitted stones and mortars.

The food was cooked in open hearths and earth ovens: A hole was dug in the ground. Hot clay balls were packed around the food to regulate heat.

The people of Poverty Point used stone and clay bowls and pots for cooking and storage. With stone chisels, the inhabitants carved containers from sandstone and soapstone, which was imported from Georgia and Alabama.

Broken pieces of containers were sometimes made into beads, pendants or plummets. In addition, Poverty Point craftsmen designed some earthen pottery. While some of these objects are simple designs, others are adorned with intricate artwork.

Archeologists have found a variety of items that verify food sources and preparation. However, the materials used to make housing and clothing disintegrate with time. So, scientists have very few artifacts to document these aspects of life.

Robert Connolly, Ph.D. Archaeologist: "There are also a couple of other problems just trying to find evidence of these houses. For example, the ridges at PP have been extensively plowed for the last 100 years or so years and it was not until 1972 when PP became a public earthwork that crops were no longer planted along the ridges. So, if people were in fact living up on the ridges, the plowing activities would have destroyed any evidence of their houses. Or certainly altered them such that we cannot recognize that evidence today."

Combining their findings at Poverty Point with evidence from similar sites, archeologists believe that a large number of inhabitants built dwellings of grass and mud on the terraced ridges.

Since no trace of Poverty Point clothing remains, scientists can only speculate as to how these ancient people dressed. They probably wore simple clothing made from animal skin.

Much more is known about how they adorned themselves. Archeologists have found jewelry including copper and galena beads. In fact, this great variety of jewelry indicates that personal status and social standing were more evident here than other American cultures of the same period.

The people of Poverty Point made many unique objects, but none were more elaborate than those having symbolic meaning. Among most southeastern Indians, such items were considered sacred or they were used as symbols of tribal identity. This might be what is represented by owls from the Poverty Point culture, which were carved in jasper. Other ordinary objects that may have been given special religious significance include those that were engraved. The animals represented are all important in the lore of southeast Indians.

Undoubtedly, these great monuments were constructed with an organizational plan that required millions of hours of labor to complete. The large earthworks and huge quantities of trade materials have led scientists to conclude that Poverty Point was not only a large society, but a sophisticated one.

Archeologists’ findings at Poverty Point present a new perspective on the evolution of society in America. Evidence suggests that ancient American hunter-gatherers lived in sophisticated communities. These prehistoric people were capable not only of harnessing natural resources for survival; but, creating magnificent works and exploring territories for the benefit the entire community. Just as Middle Eastern societies built upon the achievements of previous generations, the Poverty Point society progressed along a continuum that began with its predecessor at Watson Brake. Poverty Point lives on timelessly as the foundation of North American society.

All mounds on public land are protected from digging and artifact collecting. Access to all sites on private property is completely under the control of the landowner, and trespassing is forbidden by law. Please help us, the Louisiana Office of State Parks, the Division of Archaeology, and the people of Louisiana, in working together to help preserve and protect the nationally significant mounds of our state.

Site Layout

Production Credits

All mounds on public land are protected from digging and artifact collecting. Access to all sites on private property is completely under the control of the landowner, and trespassing is forbidden by law. Please help us, the Louisiana Office of State Parks, the Division of Archaeology, and the people of Louisiana, in working together to help preserve and protect the nationally significant mounds of our state.

A production of The State of Louisiana, Office of the Lieutenant Governor Department of Culture, Recreation & Tourism Office of State Parks and Louisiana Public Broadcasting

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation & Tourism

Kathleen Babineaux Blanco Lieutenant Governor

Phillip Jones Secretary, Department of Culture Recreation and Tourism

Dwight Landreneau Assistant Secretary, Office of State Parks

Ray Berthelot Interpretive Section Supervisor, Office of State Parks

Bo Boehringer Communications Director, Office of State Parks

Nancy Hawkins Outreach Coordinator, Division of Archaeology

Louisiana Public Broadcasting

Producer/Director Tika Laudun

Writer Adrian Hirsch

Editor Reggie Wade

Graphics Artist Steve Mitchum

Animator George Carr

Photographers Rex Fortenberry Al Godoy Tika Laudun

Narrator Pat Wallace

Native American Flutist Hawk Henries

Additional Flutist Sarah Beth Hanson

Web Design & Print Materials Tammy Crawford Denise Agnelly

Graphics Intern Drew Mills

Production Manager Ed Landry

Executive Producer Clay Fourrier

Chief Administrative Officer Cindy Rougeou

President & Chief Executive Officer Beth Courtney

Artwork Courtesy of

Jon Gibson, Archaeologist State of Louisiana Division of Archaeology

Tobin International, Ltd. (1938 aerial photo)

“Life Along The River” Web pages NPS Archeology and Ethnography Program

The University Museum, University of Arkansas

The Grand Village of the Natchez Indians Mississippi Department of Archivers and History

Center of American Archeology, Kampsville, Illinois The Southeast Archeological Center, National Park Service Artist’s reconstruction by Martin Pate

Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, Collinsville, Illinois Artists’ reconstruction by Lloyd K. Townsend and Michael Hampshire

Special Thanks

Jim Barnett Cathi Mauch Thurman Allen Andrew Barron William Iseminger John H. Jameson, Jr. Division of Archaeology The Louisiana Army National Guard C Company, 1-244th Aviation Battalion The University of Southwestern Louisiana Department of Anthropology and Sociology Staffs of Poverty Point State Commemorative Area

©1999 The State of Louisiana Office of the Lieutenant Governor Department of Culture, Recreation & Tourism www.crt.state.la.us

©1999 Louisiana Educational Television Authority www.lpb.org

Resources

In Louisiana:

Department of Culture Recreation & Tourism

http://www.crt.state.la.us

Nancy Hawkins

Louisiana Division of Archaeology

Post Office Box 44247

Baton Rouge, LA 70804

Telephone: 225-342-8170

Fax: 225-342-4480

http://www.crt.state.la.us/

National Park Service:

John H. Jameson, Jr.

Phone 850-580-3011 ext. 243

Email: john_jameson@nps.gov

http://www.cr.nps.gov/

NPS Southeast Archaeological Center

http://www.cr.nps.gov/seac/sea...

NPS Lower Mississippi Delta Projects

http://www.cr.nps.gov/seac/del...

For Additional Information:

William R. Iseminger

Public Relations Director

Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site

Illinois Historic Preservation Agency

Phone: 618-346-5160

Email: cahokiamounds@ezl.com

http://www.cahokiamounds.com

Cathi Mauch

Center for American Archaeology

Kampsville Archaeological Center

Kampsville, Illinois 62053

Phone: 618-653-1316

Jim Barnett

Director of Division of Historic Properties

Mississippi Department of Archives & History

Grand Village of the Natchez Indians

400 Jefferson Davis Blvd.

Natchez, Mississippi 39120

Phone: 601-446-6502

Email: gvni@bkbank.com

Mary Suter

Curator of Collections

University of Arkansas

Museum Bldg.

Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701

Phone: 501-575-3555